Romance’s first advantage is its flexibility. The category is not a monolith but a broad network of interlinked subgenres, which rise and fall in popularity as readers’ tastes shift. Right now “romantasy” is huge, and “sports romances” are in. “Historicals” are on the wane; “dark romance,” potentially on the rise. These changes are often cyclical, and the big subcategories eventually come back around: “About every 10 to 15 years we have a vampire surge,” Christine M. Larson, the author of Love in the Time of Self-Publishing, a multidecade history of the romance ecosystem, told me. Tying the genre together are its clear and expected plot beats—and, of course, marketing. But because the category is so broad, a romance novel can be any novel that proudly calls itself a romance.

Another important strength of the category may look at first like a contradiction. Despite its long-standing economic success, the genre—and the culture around it—retains the status of a defiant outsider. Since modern romance developed in the 1970s, these novels have been thoroughly ignored by highbrow critics and prestigious-award juries. But such exclusion may have helped their readers—and more importantly their writers and publishers—evolve into a cohort that Larson labels an “open-elite network.”

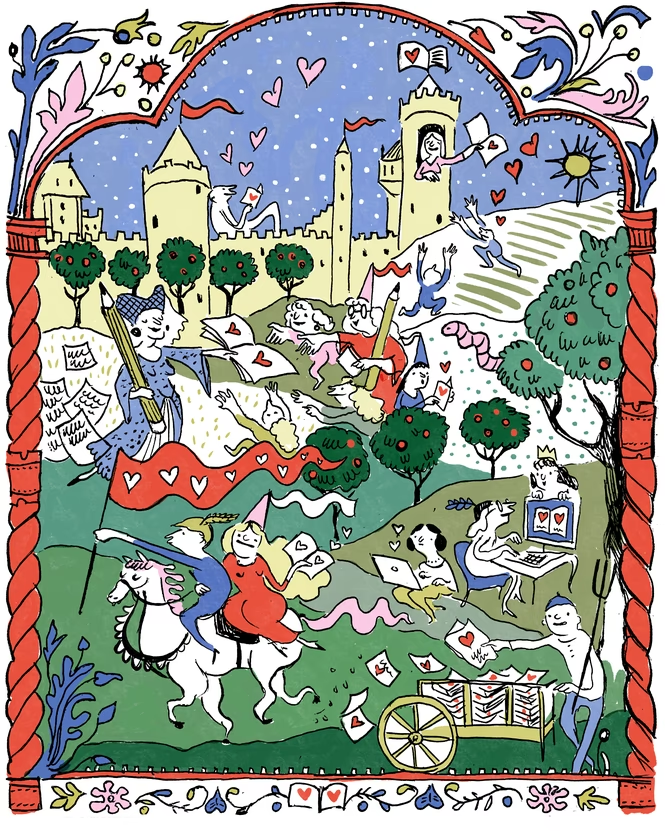

The Publishing Industry’s Most Swoon-Worthy Genre